20 Sitemap Examples + Types of Sitemaps and Best Practices

August 4, 2025

Introduction

A sitemap is exactly what it sounds like, a map of your website. It lists out the pages on your site, helping both human users and search engine crawlers navigate your content efficiently.

In other words, a sitemap acts as a guide or blueprint that shows how your site is structured and how different pages connect.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore different types of sitemaps (XML, HTML, and visual sitemaps) and look at real sitemap examples from a variety of websites.

You’ll learn why sitemaps are important for SEO and user experience, how to create and optimize them, and the latest best practices (as of 2025) to ensure your sitemap is helping, not hurting, your website’s performance in search results.

Whether you’re launching a brand-new site or managing a sprawling web presence, sitemaps can significantly improve how search engines index your pages and how users find information.

Let’s dive in!

What Is a Sitemap?

In simple terms, a sitemap is a file or page that lists all the important URLs of a website. Think of it as a directory of your site’s content.

Sitemaps can exist in different formats (which we’ll detail below), but generally they serve two main audiences: search engine bots and human visitors.

For search engines like Google, a sitemap (usually an XML file) enumerates the pages you want indexed and often includes metadata like the last modified date for each page.

For users, a sitemap (often an HTML page) provides a convenient, structured list of links to all key pages, like a table of contents for your website.

By providing a comprehensive map of your site, sitemaps ensure that no important content gets overlooked. This is especially critical for large or complex sites where some pages might not be easily reached through navigation menus or internal links.

In fact, Google’s own documentation states that most websites benefit from having a sitemap, and it “can improve the crawling of larger or more complex sites”.

In short, a well-made sitemap helps search engines find, crawl, and index your pages faster, and it can also help users (and teams working on the site) better understand the site structure.

Why Are Sitemaps Important for SEO and UX?

Sitemaps are a foundational tool for SEO because they give search engines a roadmap to discover your content. When Googlebot or other crawlers visit your site, they typically follow links from page to page.

If certain pages have no internal links pointing to them (so-called “orphan pages”), or if your website’s structure is very large or convoluted, the crawler might miss some content.

An XML sitemap mitigates this by listing all the URLs you consider important, ensuring the crawler doesn’t overlook them. This is particularly useful if:

A. You’re launching a new website-

A sitemap helps Google find all your pages faster, rather than waiting for it to gradually discover them over time.

B. Your site is large or frequently updated-

If you have hundreds or thousands of pages (like an e-commerce site or active blog), or you add new content regularly, a sitemap speeds up indexing of new and updated pages.

C. Your site has rich media or specialized content-

You can include information about images, videos, or news in your sitemap.

For example, an image entry in a sitemap helps Google understand your image content, and video entries can provide details like video duration or age appropriateness.

The more info you give search engines, the better they can serve relevant content on SERPs.

D. Your site has limited crawlability-

If some pages are only accessible via forms, search bar, or other means (i.e. not linked openly), a sitemap is a backstop to expose those URLs to crawlers.

In essence, sitemaps improve crawl coverage: Google can’t index what it hasn’t crawled, so a sitemap is like handing the crawler a shortcut to every page you care about.

Keep in mind, though, that including a URL in a sitemap doesn’t guarantee it will be indexed, but it certainly helps Google find it.

As one SEO expert notes, even if Google might discover your pages on its own, “why not make Googlebot’s job easier” by providing a sitemap?.

From a user experience (UX) perspective, HTML sitemaps can enhance navigation on large sites. Ideally, users rely on your menus and search feature to find content.

But an HTML sitemap page (often linked in the footer as “Site Map”) serves as a one-stop index of all pages in a logical hierarchy.

This can be helpful for visitors who are looking for something specific or just want an overview of what’s on the site.

For example, a corporate site might include an HTML sitemap that highlights important sections like Products, About Us, Blog, Contact, etc., in one place for convenience.

While an HTML sitemap is no substitute for a well-organized navigation menu, it supplements UX by ensuring nothing is “buried” too deep.

Moreover, HTML sitemaps create additional internal links to your pages, which can aid SEO by distributing link equity and helping crawlers reach all pages (albeit HTML sitemaps are less common today than in the past).

Another often-overlooked benefit: planning and collaboration. Web designers and developers sometimes create visual sitemaps (essentially diagrammatic site blueprints) during the planning phase of a website redesign or creation.

These aren’t for SEO per se, but they help teams visualize the site’s structure and how pages will interconnect before anything is built.

Visual sitemaps can be invaluable when working on information architecture and ensuring a coherent user journey. We’ll touch on those later as well.

Bottom line:

Sitemaps help search engines index your site more effectively (boosting SEO potential) and can help users and teams navigate complex sites (improving UX).

There’s very little downside, Google even says there’s no harm in having a sitemap, and it can only help in many cases.

So unless your website is tiny (just a few pages) and every page is naturally linked, it’s highly recommended to have a sitemap in place.

XML Sitemaps: Examples and How They Work

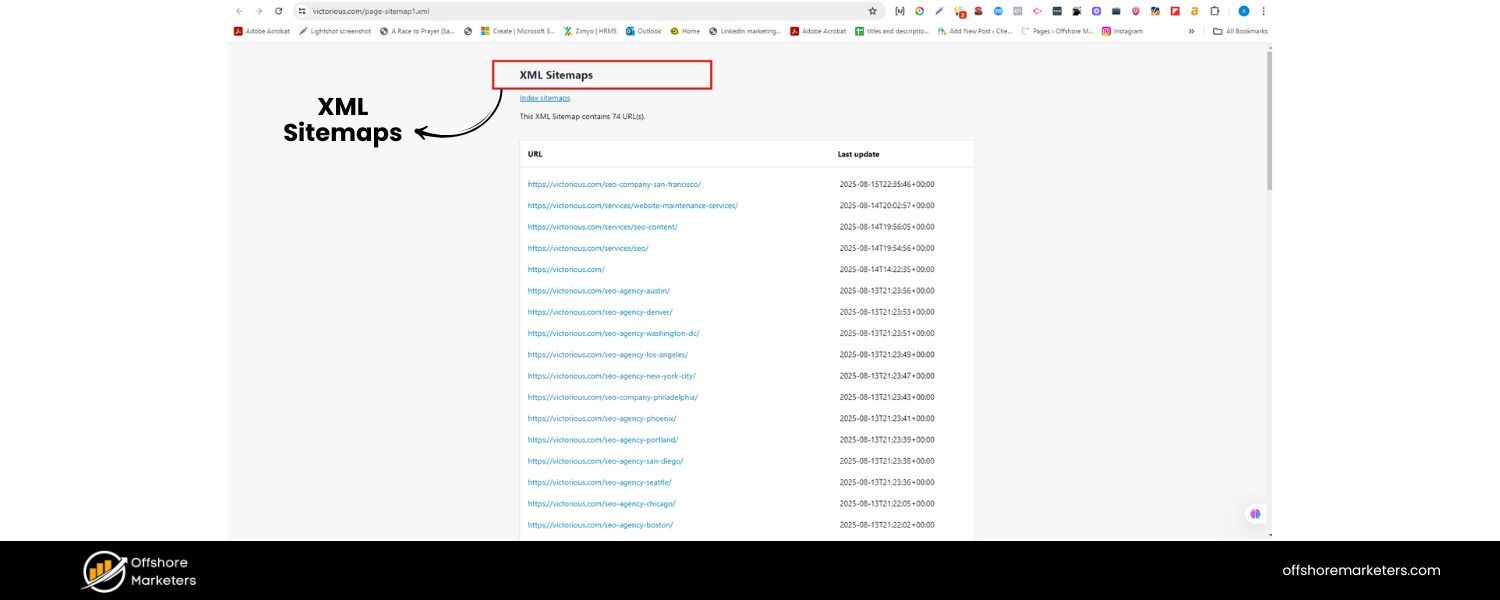

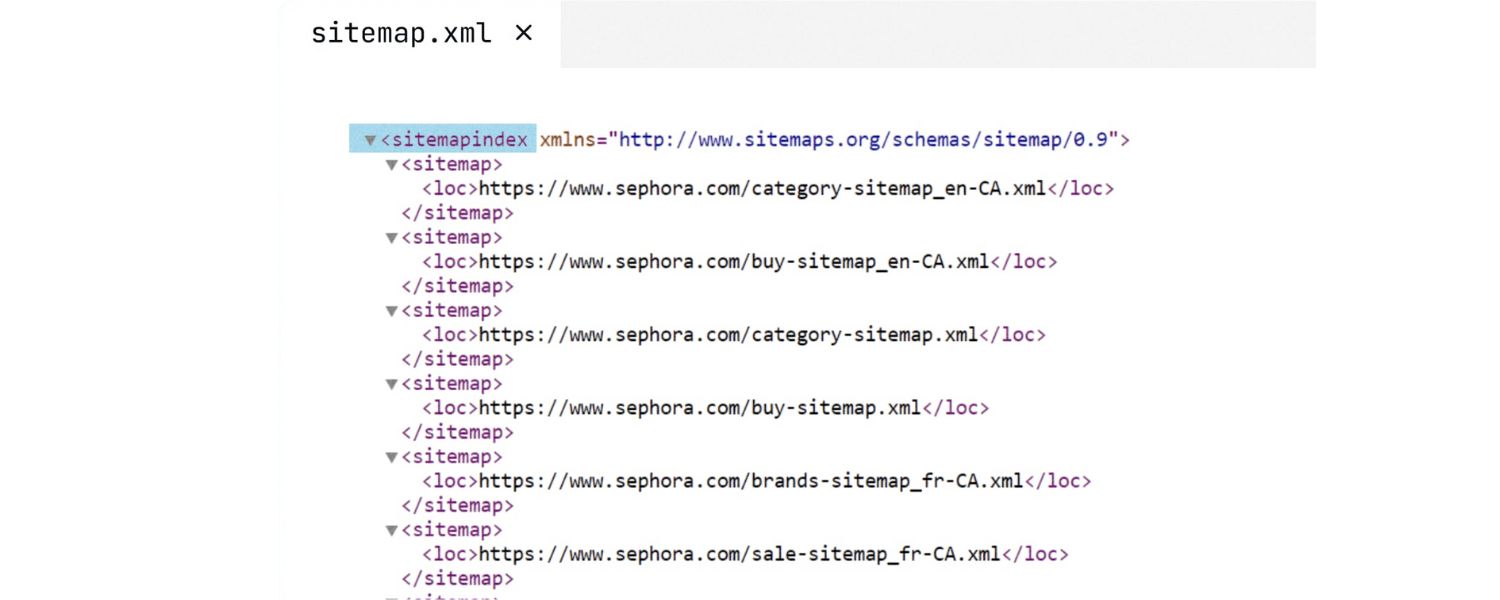

XML sitemaps are the most common type of sitemap for SEO purposes. An XML sitemap is essentially an XML file (Extensible Markup Language) that lists URLs of your site intended for search engines to crawl.

It’s not meant to be seen by users (though you can view it in a browser and it will display a bunch of XML code).

Typically, the file is named sitemap.xml and resides in your domain’s root (e.g., https://yourwebsite.com/sitemap.xml) .

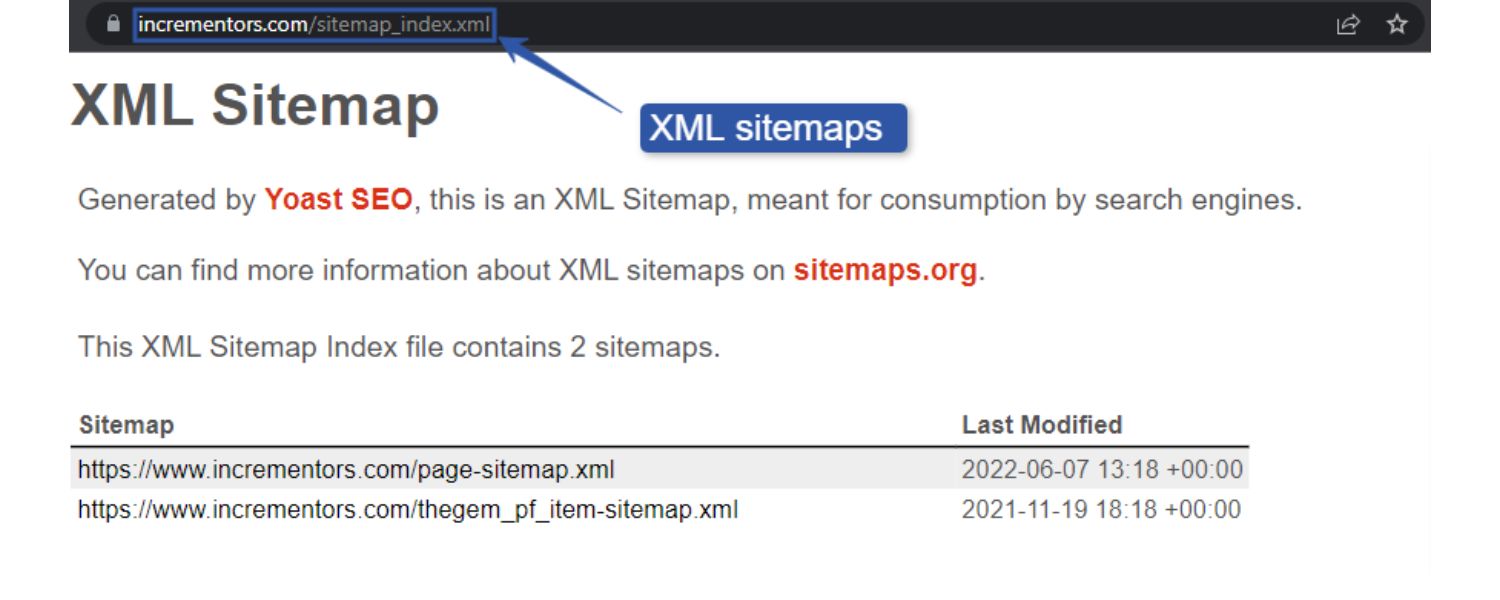

If you have multiple sitemaps (common for very large sites), there may be a sitemap index file (often sitemap_index.xml) that links to all the individual sitemap files.

An XML sitemap’s structure is simple: it contains a list of entries, each with a (location URL).

Optionally, it can include metadata like (date the page was last modified), (suggested change frequency), and (a priority hint) for each URL.

For example, you might have:

https://example.com/about-us

2025-06-01

monthly

0.8

This indicates the About Us page was last updated June 1, 2025, changes roughly monthly, and has priority 0.8 (on a scale of 0.0 to 1.0) relative to other pages.

Note: Modern search engines mostly ignore and values, Google has stated these hints are not used for ranking or crawling frequency.

The timestamp can be helpful if it’s accurate, as Google may use it to decide when to recrawl pages.

The key is not to manipulate or “fake” these values, only update when a significant change occurs on the page, otherwise leave it as-is.

XML sitemaps can also include entries for images and videos on your pages (using additional tags), as well as alternate language versions of pages (using hreflang annotations).

For instance, an e-commerce product page entry might list the image URL and caption via image:image tags.

These extras are helpful for specialized SEO (image search, video search, international SEO, etc.), but the core of a sitemap is still the list of page URLs.

Example-

1. Small XML Sitemap:

If your site is simple, your XML sitemap will likewise be simple.

Consider a tool site like HTTPStatus.io – its sitemap is just a single XML file listing the handful of pages (the tool page and some knowledge base articles).

In cases like this, don’t overcomplicate your sitemap, just list the URLs that matter, and you’re done.

Example-

2. Large XML Sitemap:

Bigger sites often use sitemap index files.

For example, Forbes.com has a sitemap index (sitemap_index.xml) which links out to a bunch of sitemaps segmented by content type and year.

There’s a sitemap for articles from 2005, another for 2006, a news sitemap, and so on. Each of those contains the URLs for pages in that category.

Forbes even includes various metadata in its sitemaps, though as noted, Google ignores things like priority/changefreq.

The important part is that Forbes’s sitemap index organizes URLs into logical groups – this is a common strategy for news sites or any site with 10,000+ pages.

By splitting URLs into multiple files, they adhere to Google’s limits (each sitemap file can be maximum 50,000 URLs or 50MB in size uncompressed) and make the sitemap content more digestible.

Another big site, Backlinko, uses a Yoast-generated sitemap index that splits URLs by posts, pages, categories of content, etc., rather than one gigantic list.

Example-

3. Massive XML Sitemap:

For extremely large websites (think millions of URLs), a multi-layered approach is needed.

Weather.com, which has tens of millions of pages (a page for weather in every city/town), has multiple sitemap indexes for different languages/regions (e.g., /en-US/sitemaps/sitemap.xml, /pt-PT/sitemaps/sitemap.xml, etc.), each of which links to further sitemap files segmented by content type (forecasts, news, videos, etc.).

Another example is eBay – with billions of listings, eBay’s sitemaps are so large that they compress them as .xml.gz files and have hundreds of them; one index file might link to 1,600+ compressed sitemap files, each containing ~40,000 URLs.

This kind of extreme case shows that sitemaps are scalable – no matter how large your site grows, you can keep adding sitemap files and indexes to cover all URLs (just make sure to stay within the per-file limits and use multiple files).

To summarize XML sitemaps:

They’re machine-friendly lists of URLs. Use them to ensure every important page on your site is presented to search engines on a silver platter.

Keep them clean – only include canonical,200-OK URLs (no error pages, broken links, or duplicate content URLs).

In the next sections, we’ll look at other types of sitemaps and then circle back to general best practices common to all.

HTML Sitemaps: Examples and Use Cases

Unlike XML sitemaps, which exist primarily for search engine bots, HTML sitemaps are designed for humans.

An HTML sitemap is basically a normal webpage (usually named “/sitemap” or “/site-map”) that lists out links to the key pages of your site in a structured, hierarchical fashion.

It often looks like a bulleted outline or a directory listing of your site’s sections and pages – think of it like the table of contents of a book, but for your website.

Users can visit this page to quickly see the site’s overall content and jump to the section they need.

Why have an HTML sitemap? For one, it can improve user navigation and ensure no page is too hidden. This is particularly helpful if you have a complex site or a very deep navigation structure.

For example, if a user can’t find a specific topic via your menus, they might check the HTML sitemap page (often linked in the footer) and find the link there.

HTML sitemaps can also assist search engines as a secondary benefit – since it’s a page with lots of internal links, crawlers will follow those links too.

In the past, Google recommended HTML sitemaps for really large sites as a backup way for crawlers to find all pages, though today XML sitemaps have largely taken that role.

Still, for user experience and accessibility, an HTML sitemap can be valuable.

Example-

Corporate HTML Sitemap: Take Forbes again. In addition to its XML sitemaps, Forbes has an HTML sitemap page at forbes.com/sitemap/.

This page isn’t just a dump of every single link; it highlights certain important categories (e.g., Leadership, Lifestyle, etc.) and pages like Newsletters.

Interestingly, it doesn’t list all site categories – presumably Forbes is curating this to avoid an overwhelming list, focusing on popular sections.

This strategy suggests using an HTML sitemap to showcase high-value pages or sections, rather than literally everything.

Another well-known example is Apple’s HTML sitemap (apple.com/sitemap/), which is neatly organized by product lines and information types, making it easy for a visitor to scan and find what they need.

Example-

E-commerce HTML Sitemap:

Consider a retailer site like Amazon’s “Sell” domain (sell.amazon.in) which has an HTML sitemap with multiple categories listed.

Or Lovevery (a children’s products site) which uses an HTML sitemap page to sort products into categories and even highlights their top products right at the top.

They even break down a category (“Play Kits”) by the child’s age range in the sitemap, so parents can quickly find age-appropriate products.

This kind of user-centric organization shows how an HTML sitemap can directly aid customers in finding products, beyond what the main menu provides.

Example-

Our Own HTML Sitemap:

Many blogs and company websites (maybe including yours) have an HTML sitemap that simply mirrors the navigation.

For instance, htmlBurger’s own sitemap page lists all main and secondary pages of their site in one place.

This is handy for visitors and also ensures that even pages buried deep in the site hierarchy have at least one direct link from the homepage (via the sitemap link).

HTML sitemaps are less common on small sites or sites where navigation is straightforward.

But you should consider an HTML sitemap if: your website has deep hierarchies or dozens of pages, if users often use search because navigation is lacking, or if your audience might not be very tech-savvy (making a clear “index” page helpful).

There’s no rule that you can’t have both an XML and an HTML sitemap, they actually serve different needs and complement each other. In fact, many big companies implement both.

One thing to remember:

An HTML sitemap should be well-organized and user-friendly itself. It should mirror the logical grouping of your site.

For SEO, the HTML sitemap page can also pass on link equity to all those pages it links to (since presumably your homepage or footer links to the sitemap, and the sitemap links to everything – it’s like creating a hub of internal links).

However, don’t rely on an HTML sitemap as a band-aid for poor navigation; it’s an aid, not a cure for UX issues.

In summary, HTML sitemaps are about usability. They’re a nice-to-have on sites where users might benefit from a birds-eye view of the content.

Many modern sites skip them, opting to just use XML sitemaps for SEO and rely on good menus for UX.

But if you run a complex site (e.g., an e-commerce store with many categories, or a documentation site), an HTML sitemap page can be a welcome addition for your visitors.

It certainly doesn’t hurt, and as a best practice, if you do have an HTML sitemap, link to it prominently (usually in the footer), so users and crawlers can find it.

Visual Sitemaps: Planning Website Architecture

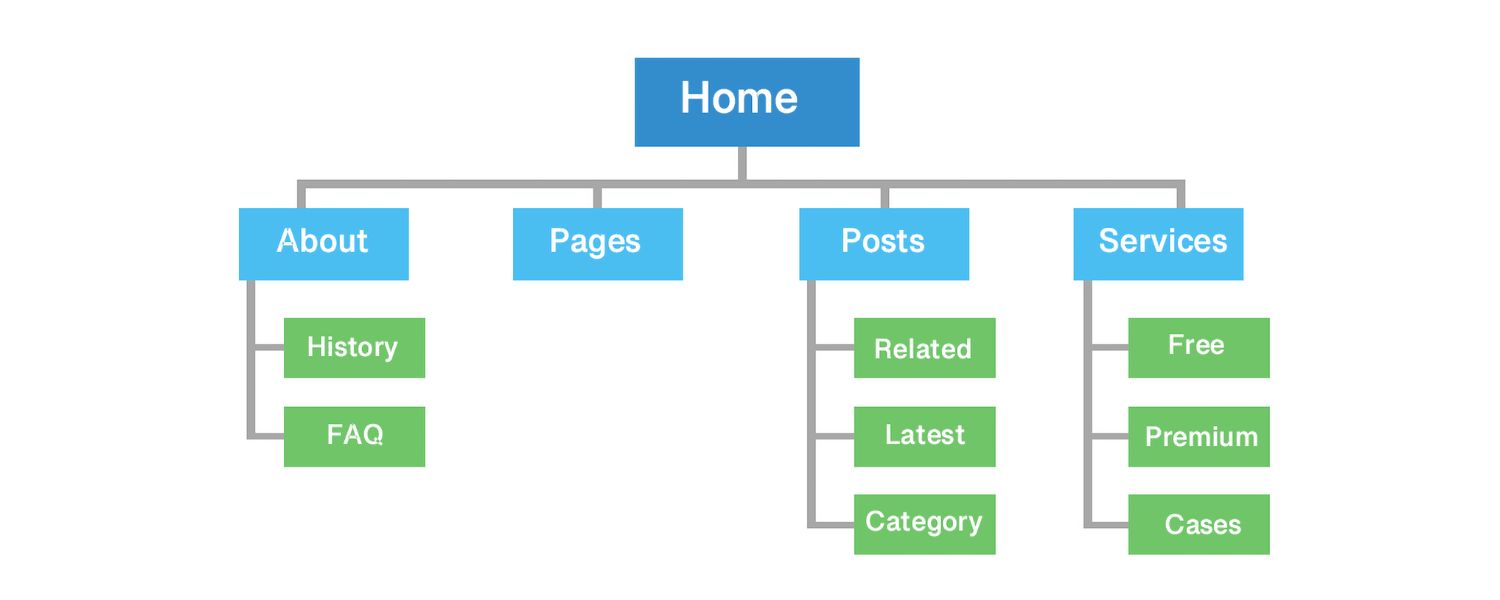

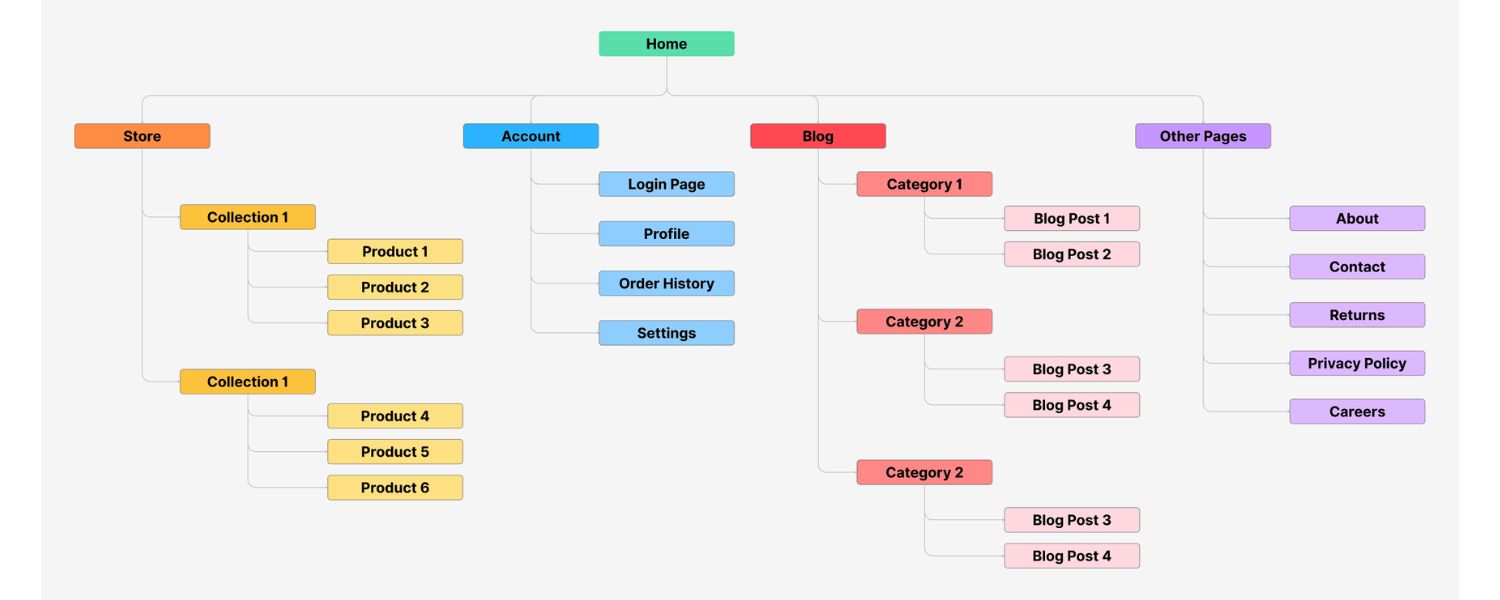

Visual sitemaps are a bit different from XML or HTML sitemaps, they are planning and design tools rather than files meant for SEO. A visual sitemap is essentially a diagram of your site’s structure.

Typically, it looks like a flowchart or mind map: boxes representing pages, connected by lines or arrows to show the hierarchy and linking between them.

Visual sitemaps are usually created by UX designers, information architects, or web developers during the early stages of a site’s design or redesign.

They help answer questions like: What are the main sections of the site? What sub-pages does each section have? How do users get from the homepage to deeper content?

In many cases, the content represented in a visual sitemap is similar to what would appear on an HTML sitemap, the same pages and structure, just drawn out graphically.

The difference is the purpose and audience. Visual sitemaps are intended for internal stakeholders (designers, clients, developers) to collaborate and ensure the site’s structure makes sense before building it.

They often include notes about functionality or content types on each page, which an HTML/XML sitemap wouldn’t convey.

Example-

Website Planning:

Imagine you’re creating a new website for a university.

Before writing a single line of code, you might create a visual sitemap showing the Home page, then top-level sections like Admissions, Academics, Research, About, etc., each with their sub-pages branching out.

This can be done on paper, or using tools like FlowMapp, Lucidchart, or even PowerPoint. In fact, tools like FlowMapp specialize in visual sitemapping and come with templates for common project types.

They offer pre-made examples for an e-commerce site, a SaaS website, a corporate site, and so on, these templates suggest how to structure those types of sites for optimal user flow.

For instance, a FlowMapp e-commerce sitemap template will illustrate a logical structure guiding users from the homepage to category pages to product pages in as few clicks as possible.

Visual Sitemap vs Information Architecture:

You might hear the term information architecture (IA), which refers to the broader discipline of organizing and labeling content effectively.

A visual sitemap is one output of the IA process, representing the planned hierarchy and relationships.

It’s worth noting the distinction: Information Architecture defines the content structure and navigation rules, while a sitemap (visual) is a concrete diagram of the site’s pages following that architecture.

As one case study put it, the IA focuses on content grouping and labeling, whereas the sitemap “shows the pages and their hierarchy” and how a user might traverse them.

Modern Developments- AI-Generated Sitemaps:

In 2025, we will even have AI tools that attempt to generate visual sitemaps.

Tools like Octopus.Do and Relume allow you to input a prompt (e.g., “Create a sitemap for a university website”), and they will produce a draft visual sitemap structure.

Early tests show these AI-generated sitemaps aren’t perfect – you’ll still need to refine and edit the structure – but they can save time by giving you a starting point instead of a blank canvas.

This is a cutting-edge development for site planning, though not directly related to the XML/HTML sitemaps that go on your live site.

It does, however, underscore how important sitemapping is considered in web design that even AI is being applied to it!

In summary, visual sitemaps are all about designing a site’s structure with usability in mind. They’re the blueprint you create before building the site.

While they don’t get uploaded to your website for Google to crawl, they indirectly contribute to SEO by ensuring you have a logical site structure and navigation, which leads to better internal linking and happier users (which search engines ultimately reward).

If you’re undertaking a site redesign or starting a large project, don’t skip the visual sitemap stage, it can reveal holes in your planned content or navigation scheme on paper before those issues cost time and money later.

Now that we’ve covered all three types of sitemaps (XML, HTML, and visual), let’s compile some best practices to help you make the most of them.

Sitemap Examples from Real Websites

To put things in perspective, here’s a quick roundup of how different kinds of websites leverage sitemaps, and what you can learn from them:

1. Blog Website (Content Site)

Cup of Jo, a long-running blog, auto-generates an XML sitemap that organizes URLs by content type: posts (broken into 8 sub-sitemaps for 10+ years of posts), pages, products, authors, etc…

One mistake they made is including an “affiliate links” sitemap that doesn’t add much value, it’s basically pages with single images.

The lesson: Include only valuable pages in your sitemap (Cup of Jo would be better off excluding that affiliate links section).

Another content site, NerdWallet, has a main sitemap index plus separate regional sitemaps for their UK, CA, and other country sections.

Despite having tens of thousands of pages, NerdWallet’s sitemaps are straightforward (just URL and lastmod), proving that even large blogs can keep sitemaps clean and simple.

For blogs, it’s also wise to list posts in reverse chronological order in a sitemap or split by year/category, so new content is highlighted.

And don’t include tag or category pages in the sitemap if they don’t add unique value (to avoid duplicate content).

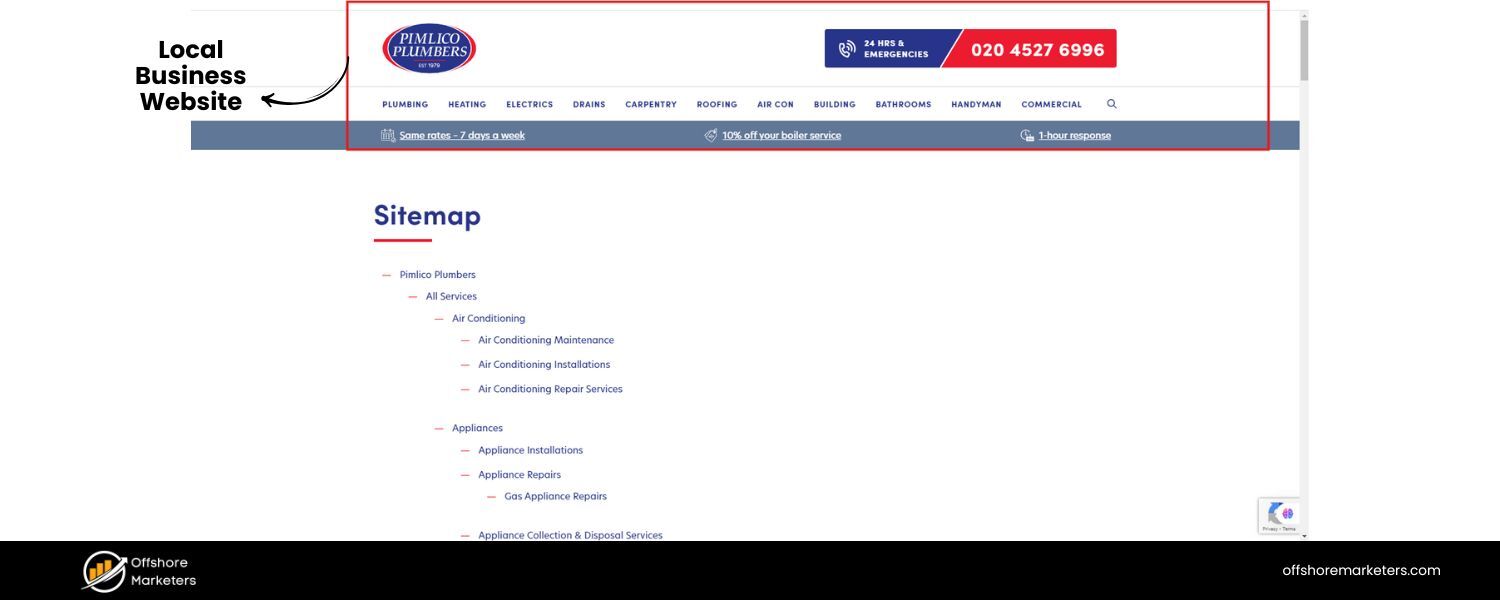

2. Local Business Website

Pimlico Plumbers (a local services business in London) uses a sitemap index that includes a dedicated sitemap for all their service location pages.

This is smart, if you serve multiple locations or service areas, make sure they’re all listed, possibly in their own section. Pimlico’s “location-sitemap.xml” helps Google easily find each borough’s service page.

If you have just one location or a simple site (like The Wild Rabbit inn, which has just posts, pages, events in its sitemap), a single sitemap is fine.

The main takeaway for local businesses:

Include your location or contact pages in the sitemap (you want those indexed!), and if you have many locations, consider grouping them in a separate sitemap for clarity.

A. E-commerce Website

We touched on Gymshark earlier, their sitemap index smartly splits content into products, collections, and pages.

They even have separate sitemaps for different language sites and hreflang references, which is important for international SEO.

Another store, Ruggable, keeps it extremely simple: just four sitemaps – one each for products, pages, collections, and blog posts.

Even though Ruggable has thousands of products, they fit them in a single product sitemap (over 1,000 URLs, well under the 50k limit).

This shows that logical organization by content type (and splitting by category if needed) works well in e-commerce.

Also, don’t include variant or filter URLs, e-commerce sites often have URL parameters for sorting or filtering which should be kept out of sitemaps to avoid duplicate content issues.

Make sure every in-stock product is in the sitemap, and consider removing or flagging discontinued product URLs (if they 404 or redirect) so they don’t clutter the sitemap.

B. Large Scale Site

Weather.com and eBay demonstrated the use of multiple levels of sitemaps and compression for scale.

If your site is anywhere near that size, the key learnings are: use sitemap index files to categorize sitemaps (by site section, language, or content type), and feel free to compress sitemaps (.xml.gz) to make file transfers efficient – Google will read gzipped sitemaps just fine.

Also, for huge sites, focus on including your most important pages in sitemaps rather than every conceivable URL.

For instance, a site like eBay probably doesn’t try to list all billions of item URLs at once, but they ensure some sitemap file covers each major segment.

The average website owner won’t have to worry about hitting the 50k URL limit, but if you do, just remember you can always add another sitemap file and link it in a sitemap index (and if you exceed 50,000 sitemaps in the index – unlikely – you can even have multiple index files!).

C. SaaS or Corporate Site

SaaS companies often have key pages like features, pricing, login, blog, support, etc. A well-structured sitemap will list all these.

Backlinko’s guide mentioned that a well-designed corporate sitemap makes sure Google indexes high-value pages like investor relations, press releases, etc., which might not be heavily interlinked on the public site.

So for a corporate or SaaS site, double-check that your sitemap isn’t missing sections like careers, media resources, case studies, anything that might be a bit tucked away but is still important content.

These examples reinforce that one size does not fit all for sitemaps, you should tailor your sitemap strategy to your site’s content and goals.

However, across all these scenarios, some common principles emerge. In the next section, we distill those into best practices you should follow when building your own sitemap.

Sitemap Best Practices

Creating a sitemap is not just about throwing every URL into a file. The quality and relevance of your sitemap matter.

Here are some best practices and tips to ensure your sitemap is effective and SEO-friendly:

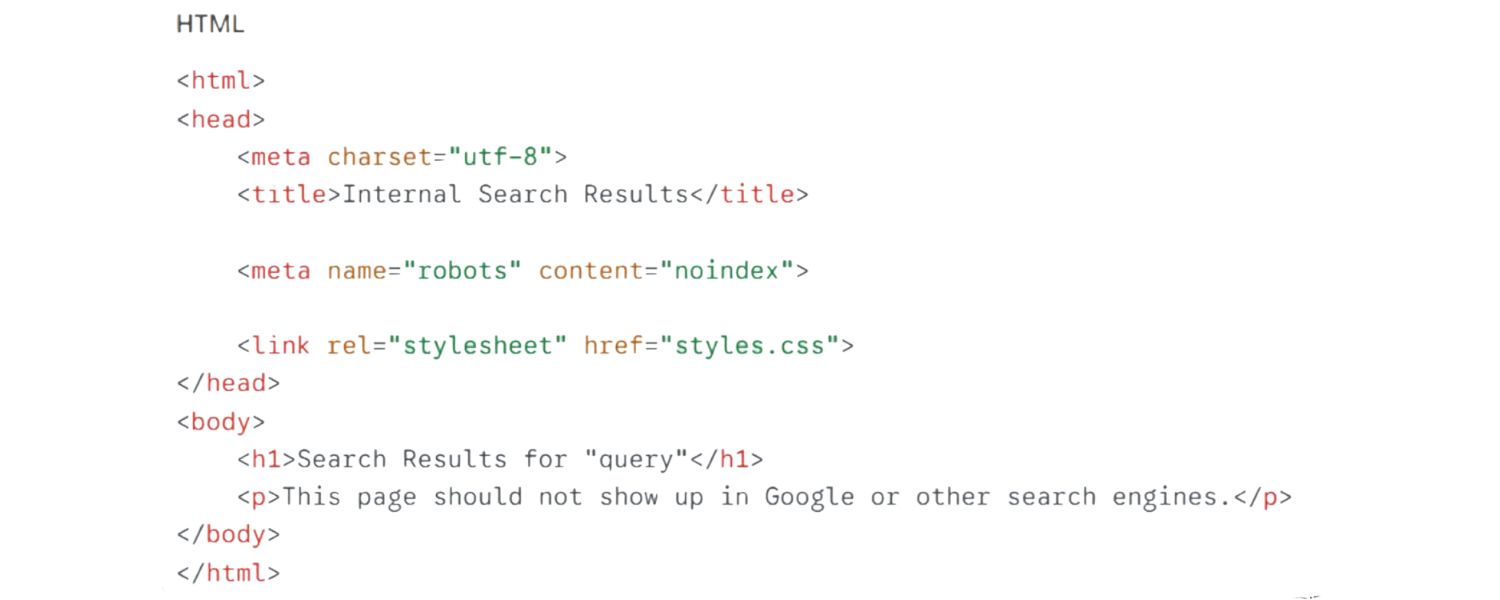

1. Include Only Important, Indexable Pages

Only list the URLs that you want search engines to index and show to users. Do not include pages with a “noindex” meta tag (pages you’ve explicitly marked to exclude from search results).

Also avoid utility pages like login screens, admin pages, thank-you pages, or any URL that isn’t valuable for search visitors. Every page in your sitemap should offer unique content and value.

For example: Exclude duplicate content pages, session-ID URLs, or alternate language pages that aren’t canonical (use hreflang in the sitemap or separate sitemaps for those).

The presence of non-indexable or low-value pages confuses crawlers and can waste crawl budget.

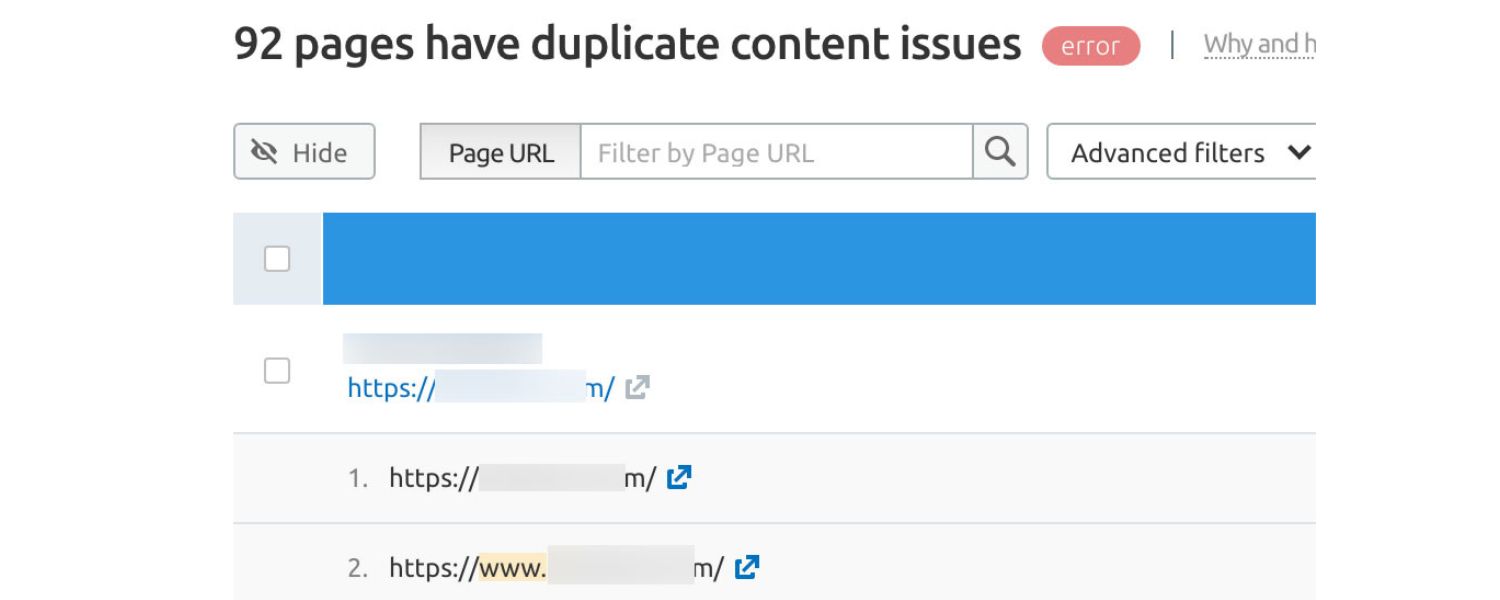

2. Use the Canonical Versions of URLs

Make sure the URLs in the sitemap exactly match your canonical URLs (the preferred version of a page).

If your site has both http:// and https:// or both www and non-www versions, list only the canonical ones (likely the HTTPS, www or whichever you use).

Don’t include URLs that redirect to another URL; only include the final destination URL that is the actual page. For instance, if /old-page redirects to /new-page, only /new-page belongs in the sitemap.

3. Avoid Including Error or Duplicate URLs

This should go without saying, but ensure no broken links (404s) or server errors (5xx) are in the sitemap. If a page is temporarily down or removed, update your sitemap accordingly.

Similarly, if you have two URLs serving the same content (duplicate pages), pick one (preferably implement a canonical tag on it) and include only that one in the sitemap.

Remember, sitemaps are for important, unique content – if it’s not something you’d want showing up in search results, keep it out of the sitemap.

4. Keep Sitemap File Sizes Under Limits

Google’s guideline is 50,000 URLs or 50 MB per sitemap file.

Most sites never hit this. But if you do, split your sitemap into multiple files (e.g., sitemap1.xml, sitemap2.xml, etc.) and create a sitemap index to list them all.

Many CMSs do this automatically (for example, WordPress with Yoast might break posts into post-sitemap1.xml, post-sitemap2.xml, etc.).

Also, you can compress sitemaps using gzip if they’re large – just ensure the uncompressed count/size is within limits.

Pro tip: Consider segmenting sitemaps by type (blog posts, products, videos, etc.) even if you aren’t at the limit.

This can make it easier to manage and debug issues (and as a slight benefit, search engines might crawl important sections more often if they’re in their own file).

5. Use a Dynamic Sitemap (Auto-Update)

Whenever possible, set up your sitemap to update automatically when you add or remove content.

Most modern platforms and plugins handle this – for instance, Shopify auto-generates and updates sitemaps out of the box, and WordPress plugins like Yoast or RankMath will update the sitemap whenever you publish or delete a post.

A dynamic sitemap ensures you don’t have to manually edit the file and prevents stale data.

If you maintain a static sitemap manually, set a reminder to review it periodically so new pages aren’t missing and removed pages are dropped.

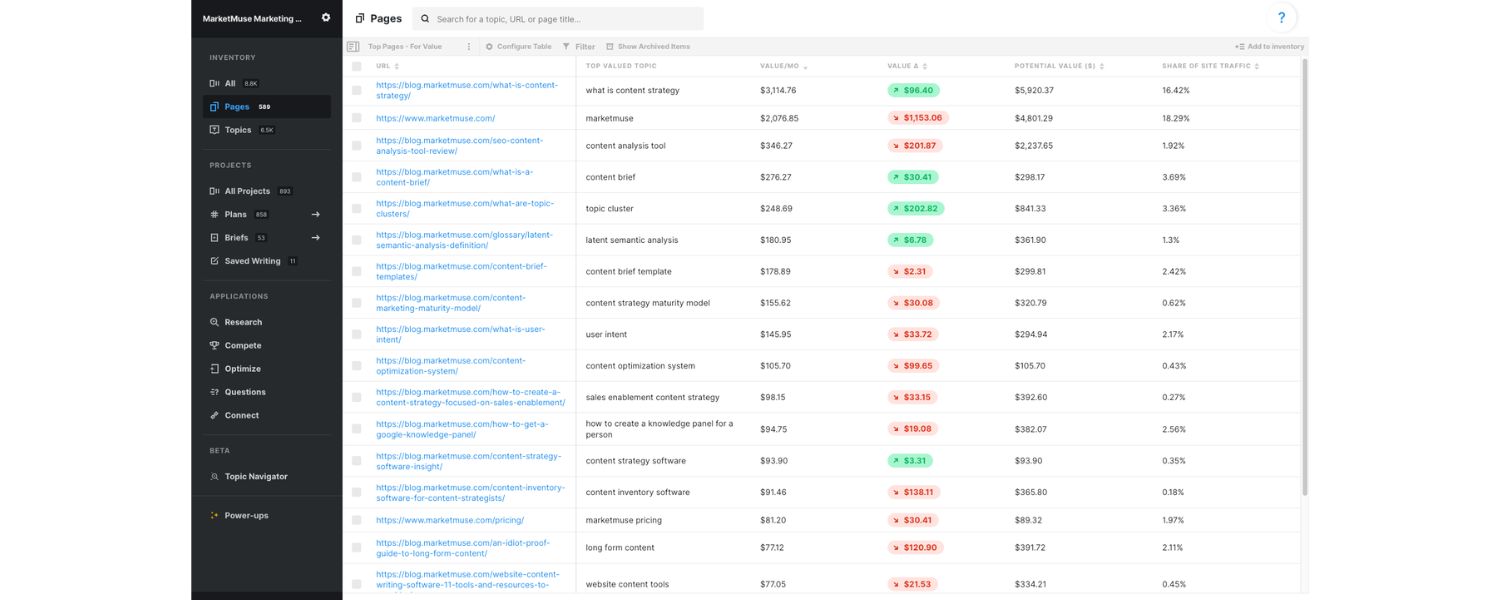

6. List All High-Value Pages

Sounds obvious, but double-check that every page you care about is indeed present. It’s easy to overlook sections.

For example, on an ecommerce site, ensure all product category pages are included, not just product pages, those category pages can rank too.

On a blog, ensure important evergreen pages (like an FAQ or resource library) are listed even if they’re not in the main blog feed.

If you have multiple sitemap files, verify that together they cover everything you want indexed. If you do intentionally leave something out (say, thin pages or tag archives), that’s fine as long as it’s deliberate.

7. Place Sitemaps Where Search Engines Can Find Them

Usually this means keeping your XML sitemap at the root (/sitemap.xml).

If you use a different URL or have multiple sitemaps in subdirectories, that’s okay – just make sure to reference them in a robots.txt file.

It’s a best practice to add a line in your robots.txt like Sitemap: https://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml . This helps search engines discover the sitemap on their own.

Additionally, linking to your HTML sitemap (if you have one) from the footer or homepage ensures both users and crawlers can navigate to it easily. In short, make your sitemap accessible.

8. Exclude “Noindex” or Paginated Content

As mentioned, pages that you’ve marked as “noindex” (like perhaps a privacy policy or certain thin content pages) should not appear in the sitemap.

Also, if you have paginated content (like page 2, page 3 of an article or category), generally those aren’t great to include either – focus on the main URL.

Google might eventually index page2, page3 if they find them through links, but they’re not usually “landing pages” you want to promote.

If you do include pagination, ensure the canonical points to page1 and consider not listing all page variations in the sitemap.

9. Prioritize Real Updates in

If you use timestamps, only update them when the page’s content truly changes significantly.

Don’t game this by bumping dates to try to get more frequent crawls, Google is aware of that tactic. It’s better to omit and entirely (since Google ignores them), and just use accurately.

An accurate can signal Google that a page that hasn’t been touched in two years maybe doesn’t need recrawling often, whereas a page you edited yesterday does.

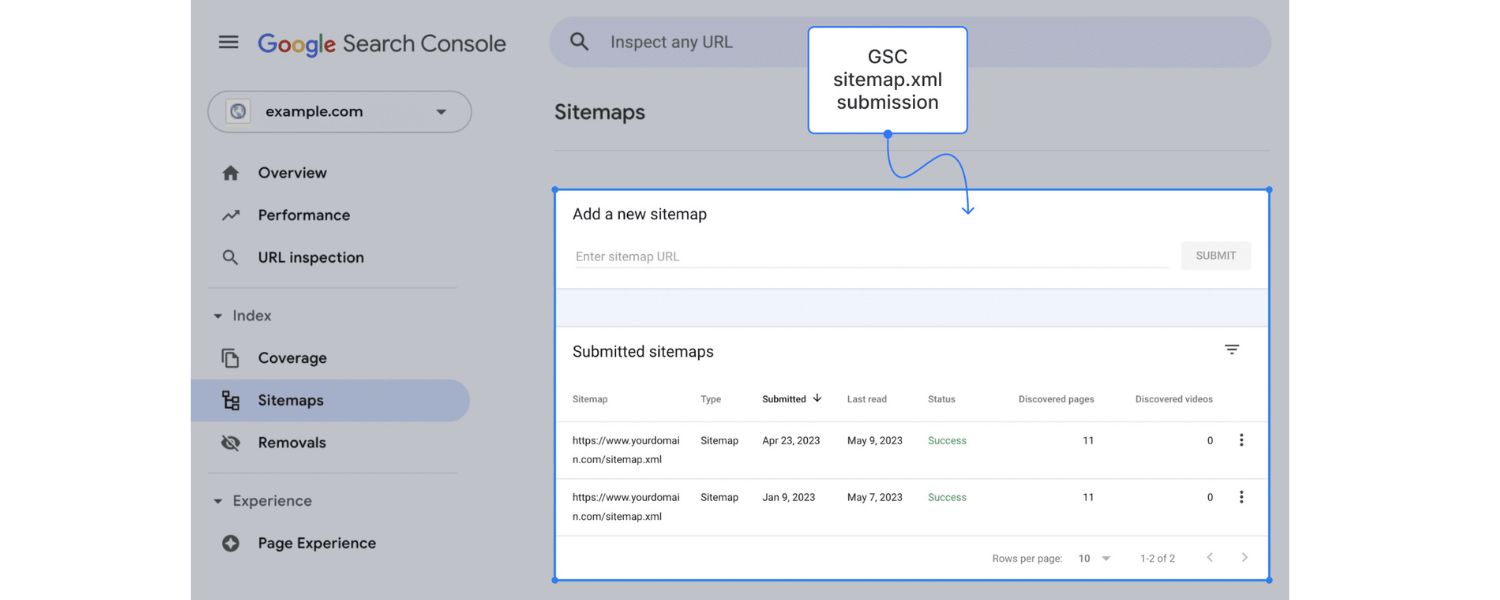

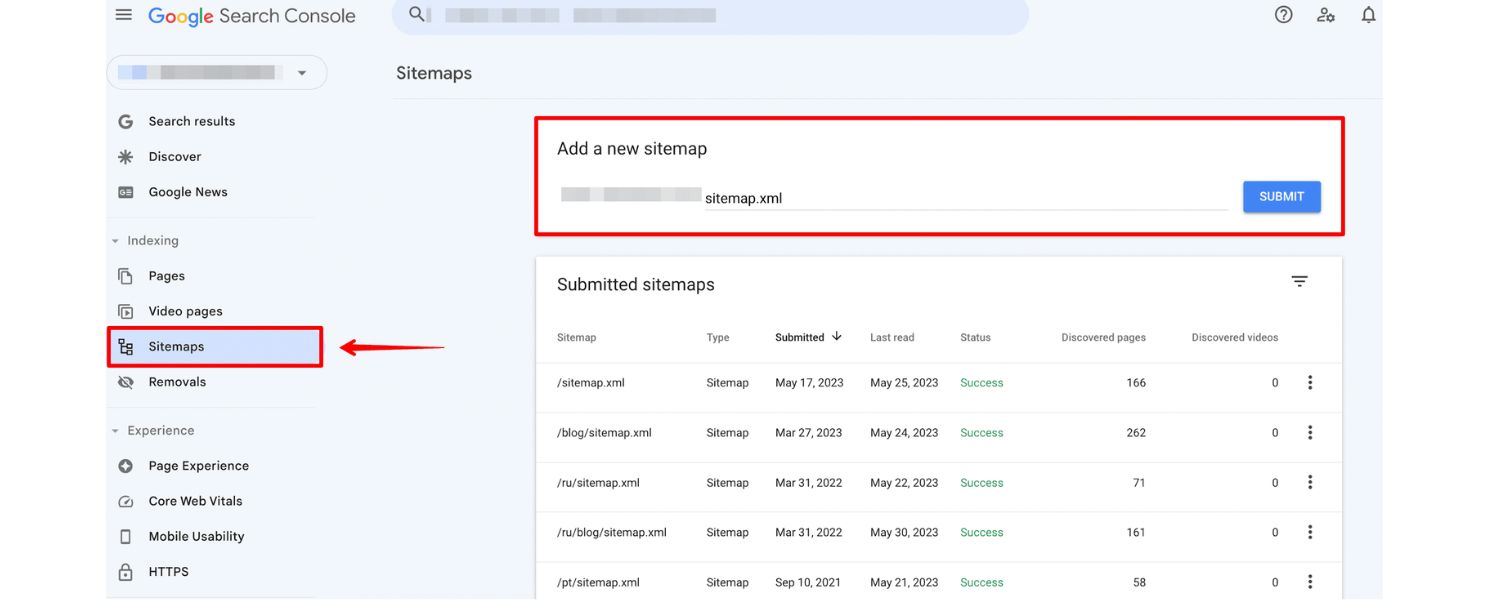

10. Submit Your Sitemap in Google Search Console

While Googlebot may find your sitemap from robots.txt or by crawling, there’s no reason to wait. Use Google Search Console (GSC) to submit your sitemap URL directly.

This often prompts Google to fetch it immediately and gives you feedback – GSC will report if the sitemap was fetched successfully, how many URLs were indexed, and if there are any problems (like “URLs not allowed” or broken links).

It’s a quick step:

in GSC, go to the “Indexing > Sitemaps” section, enter your sitemap URL, and hit submit. Do the same for Bing via Bing Webmaster Tools, if you care about Bing.

Also, if you ever make major changes (like split your sitemap into many files differently), you can remove old sitemap entries in GSC and resubmit.

GSC’s Sitemaps report and Index Coverage report are your friends to verify that the pages in your sitemap are being indexed as expected.

If you see in GSC that a large portion of your sitemap URLs are not indexed, it could highlight issues with those pages (content quality, duplicate, etc.) that you may need to address.

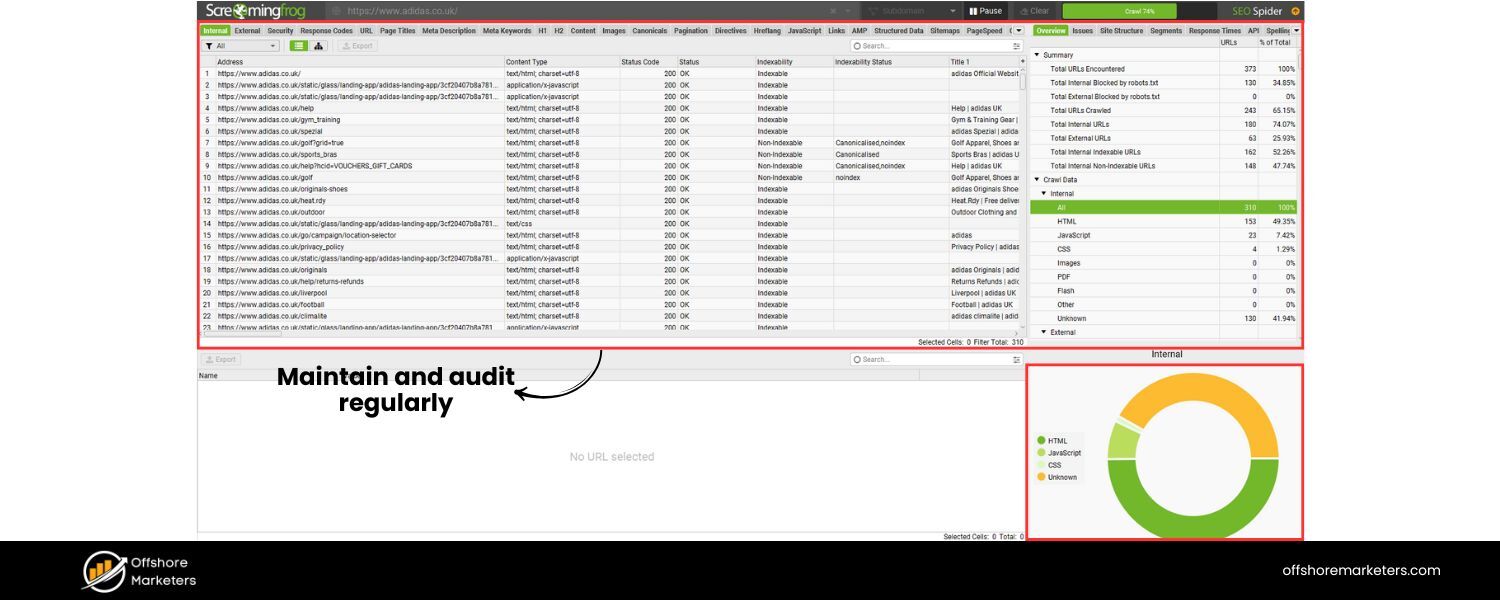

11. Maintain and Audit Regularly

A sitemap is not a “set it and forget it” if your site changes often. Every few months (or more frequently for very active sites), audit your sitemap.

Ensure obsolete URLs are removed (e.g. discontinued products that now 404, old campaign landing pages, etc.), and new sections are added.

Also check for errors – for instance, sometimes a CMS might accidentally list a draft page or an admin page if configured incorrectly.

Tools like SEO crawlers or site audit tools can automatically scan for sitemap issues.

For example, Semrush’s Site Audit tool or Screaming Frog can flag things like “URL in sitemap not found (404)” or “ Sitemap URL is blocked by robots.txt” etc., which you can then fix.

Keeping an error-free sitemap ensures Google can trust it and use it effectively.

Following these best practices will help make your sitemap a powerful asset rather than just a neglected XML file.

To recap the most critical points: keep it clean, comprehensive, and up-to-date. Now, let’s briefly cover how you can create a sitemap (or improve the one you have) with the tools available.

How to Create and Optimize Your Sitemap

Creating a sitemap doesn’t have to be complicated. Here are some approaches:

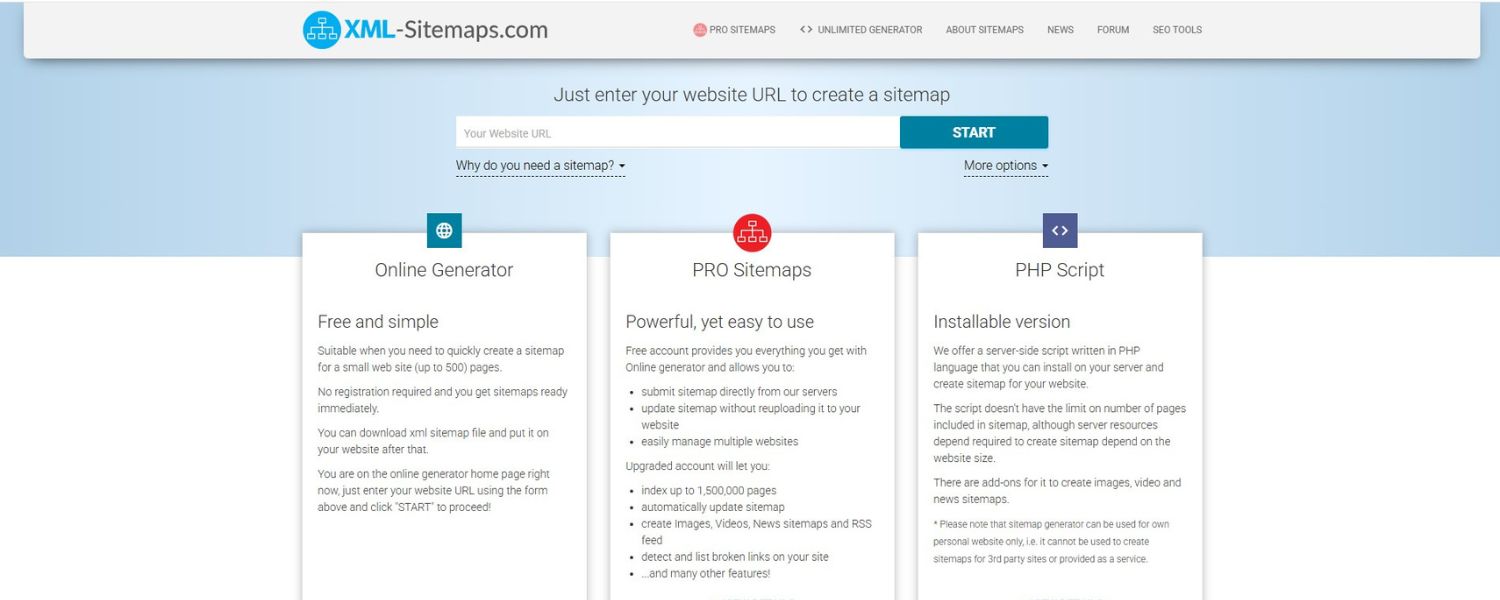

1. Use a Sitemap Generator or CMS Plugin

This is the easiest route for most. If you’re on WordPress, SEO plugins like Yoast SEO or Rank Math can automatically generate an XML sitemap for you with a click (and keep it updated).

Other CMSs have similar extensions (Joomla has JSitemap, Drupal has a Sitemap module, etc.).

There are also free online sitemap generators, for example, XML-Sitemaps.com, Screaming Frog (for more advanced control), or even small tools that will crawl your site and produce a sitemap file.

Semrush published a list of top sitemap generator tools in 2025, which include both online services and software. The key is to choose one that suits your needs and ensure it’s configured to include/exclude the right URLs.

For an HTML sitemap, if using WordPress, you can find plugins specifically for that (like Simple Sitemap plugin which lets you create a nicely formatted HTML sitemap page easily).

2. Manual Creation (for static sites or full control)

If you have a small static site, you can hand-craft an XML sitemap using a simple text editor. Follow the official sitemaps.org protocol for the XML format – essentially wrapping your URLs in the proper tags.

However, manual sitemaps become unmanageable once you have more than a handful of pages, and you’ll need to remember to update it with every site change.

It’s usually not worth the effort when tools can do it instantly.

One hybrid approach some use: generate a base sitemap with a tool, then manually tweak it (e.g., remove some URLs or add lastmod info) before uploading. Just be careful that if you regenerate, you don’t overwrite those tweaks.

3. Leverage your Server and Framework

Some modern web frameworks have built-in sitemap support.

For example, Next.js or Gatsby (popular JavaScript frameworks) often have plugins to auto-generate sitemaps at build time.

If you’re inclined toward coding, you can write a simple script that outputs your URLs in XML format. Again, for most, a plugin or generator is simpler.

Once generated, validate your sitemap. You can use the Google Search Console testing tool or online validators to ensure the XML is well-formed and all links work.

Also, if you have multiple sitemaps, ensure the index file correctly lists them.

After creation, remember to submit it to search engines (as noted in best practices) and monitor. Over time, as you add content, keep an eye on your sitemap. It should evolve with your site.

One more tip:

Indicate your sitemap in robots.txt (example: add Sitemap: https://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml at the end of your robots.txt).

This is a straightforward step that can help search engines discover the sitemap even if you forget to submit it manually.

By following these steps and tips, you’ll ensure your sitemap is working hard for you in the background, helping search engines crawl your site better and perhaps even giving you a slight edge over sites that neglect their technical SEO basics.

Conclusion & Next Steps

Sitemaps might not be the flashiest aspect of SEO, but they are undeniably important for your site’s crawlability and indexation.

We’ve looked at a wide range of sitemap examples, from small blogs to giant marketplaces, and the common thread is clear: a well-structured sitemap makes it easier for Google and other search engines to find and understand your content.

In tandem with a solid internal linking strategy and great content, a proper sitemap can help maximize your visibility in search results.

Now it’s time to apply these insights. If you don’t have a sitemap yet, go ahead and generate one using the method that fits your platform.

If you already have a sitemap, take a few minutes to review it against the best practices above – you might be surprised by what you find (outdated entries, missing sections, etc.).

Clean it up and resubmit it to search engines for a fresh crawl. For those with HTML sitemaps, consider if it’s up-to-date and easily accessible to users; it might be due for an update as your site grows.

Remember, creating a sitemap is just the first step. Going forward, integrate sitemap checks into your site maintenance routine.

For example, whenever you publish a big batch of new content or remove old pages, verify the sitemap reflects those changes.

Keep an eye on Google Search Console for any crawl errors or indexing anomalies related to your sitemap, it will literally tell you if something’s amiss.

Finally, if you found this guide helpful, feel free to share it with others who might benefit. Optimizing technical SEO elements like sitemaps can often yield quick wins for indexing and traffic – and yet many websites overlook it.

By implementing the tips and following the examples we discussed, you’re positioning your site a step ahead.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)